Where have all the good men gone

And where are all the gods?

Where’s the street-wise Hercules

To fight the rising odds?

Isn’t there a white knight upon a fiery steed?

Late at night I toss and I turn and I dream of what I need

What makes a good romantic hero and heroine? I include both because today’s romantic heroine doesn’t wait for the hero to rescue her from circumstances, or from the villain. She is no victim, seeking out a safe space from microaggressors.

Although she may be limited in the actions she can take because of societal expectations – as Marion Halcombe laments in Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White – or through physical limitations, our romantic heroine is, nonetheless an active participant in the world around her.

So while I talk of heroes here, I don’t mean to diminish the agency women have in romance novels, but let’s face it – women read romance novels to experience the feeling of falling in love again – that heady, breathless, excitement that comes with a new relationship, one you have hopes for but there is still uncertainty of the unknown that diminishes as our couple get to know one another and move towards the fulfilling ‘happily ever after’.

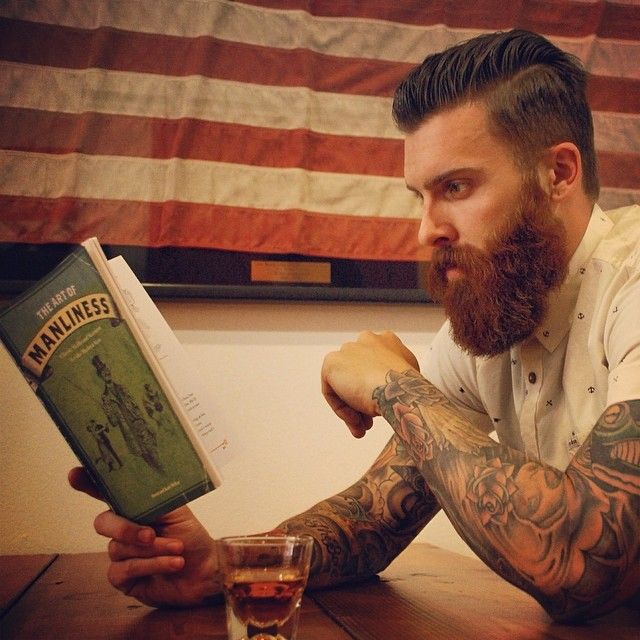

To that end, we need to believe in these heroes. They need to have the characteristics of manliness that we can be satisfied at the end that the heroine has made the right choice in falling in love with.

An off-putting alpha male

Manliness is often conflated with alpha male obstinacy, pig headedness, brawn over brains but I think that is to miss the point entirely.

There are plenty of men who can’t muscle their way out of trouble for whatever reason and they are no less masculine. In fact there are no shortage of romance novels in which the hero is not physically whole.

There is also a secondary type of hero who would rather talk his way out of trouble.

What makes a hero is moral clarity. We see this in all manner of stories both romantic and action/adventure. He is the hero who could kill the villain in cold blood that doesn’t, he is the man who puts his life in danger to pull the villain off the cliff edge instead of leaving him drop to death – the fact the many villains die at the end is as a result of their own actions, not the hero’s.

When the hero does kill, it is done in self-defense, to protect of the defenseless or in the service of an objectively moral good (defeating the Nazis, defending the planet from malevolent aliens, etc).

Even if he is not called upon to take such drastic measures, our hero knows who he is as a man our hero will ultimately be faced with an convenient option which is wrong or inconvenient option which is right. He may struggle to make his decision, but ultimately it will be the objectively right one.

Which at nearly 500 words brings me to my point – a fascinating article this month by Brendan O’Neill called The Crisis of Character. Over much longer than 500 words, he addresses the malaise of the 21st century, the lack of moral clarity when it comes post-modern thinking.

Nothing speaks more profoundly to the crisis of character than the phrase, ‘I identify as…’. In the past, individuals were. ‘I am a builder.’ ‘I am a mother.’ ‘I am a Jew.’ There was a confidence, a certainty, to their sense of identity, and to their declaration of it. ‘I am.’ Today, individuals identify as something. ‘I identify as working class.’ ‘I identify as non-binary.’… The rise of the i-word in our definition of ourselves, the ascendancy of what is called ‘self-identification’, is one of the most notable developments of the 21st century so far. It speaks to a shift from being to passing through; from a clear sense of presence in the world to a feeling of transience; from identities that were rooted to identities that are tentative, insecure, questionable.

Who sounds more heroic:

The guy who says, “I am a man.” or,

The guy who says, “I identify as male.”?

That certitude gives confidence that when it comes to making those moral decisions, our hero will make the right one regardless of the blowtorch of public opinion. Even if it means he has to stand alone when everyone else has capitulated.

O’Neill speaks of how language has been altered to fit an alternate reality (I address the subject too) where an objectively false notion is being foisted on society at large. The disease of narcissism is uncritically accepted and the demands of external validation become increasingly louder, drowning out the still small voice of conscience, moral clarity and objective truth.

No wonder romantic fiction is increasingly popular – where men and women, as flawed as we all are as human beings, make compelling and objectively right choices on the journey to a satisfying and life-long happily ever after.